Bonds are among the most confusing and misunderstood of asset classes. This makes it harder to choose a bond fund suitable for your objectives and exposure to risk.

Bonds are often lazily mischaracterised as ‘safe’. They can be anything but. A major problem is the term ‘bonds’ covers a vast menagerie, running from benign to beastly. Yet the bond funds [1] that most of us need can be boiled down to a handful of choices.

2022 has been historically bad for bonds. But we’d still argue they belong in a diversified portfolio, along with equities, cash, and perhaps gold.

It’s all part of weatherproofing your wealth against whatever economic switcheroos come next.

Please see our refreshers on the point of the different bond asset classes [2] and whether bonds are a good investment [3]. Our bond jargon buster [4] is also worth a quick read if you’d like a clear definition of the key terms.

How to choose a bond fund: the quick version

To choose a bond fund [5] that’s best for your needs, you need to match their properties to your investment goals and the threats that could derail you.

The following table maps portfolio demands against the most appropriate bond fund type to fulfill the brief:

| Role | Bond fund type |

| Diversify against deep recession | Long government bonds |

| Protect against rising interest rates | Short government bonds |

| Finance near-term cash needs | Short government bonds |

| Balance current risks vs reward | Intermediate government bonds |

| Protect vs unexpected inflation / stagflationary recession | Short index-linked government bonds |

Note: UK government bonds are called gilts, and the terms are used interchangeably.

That’s the York Notes version of the story. But it’s a good idea to scratch beneath the surface to understand the pros and cons.

Long government bonds, for example, are the best defence against a classic deflationary recession. But they’re a liability in stagflationary conditions.

And while index-linked government bonds are the best protectors against a sudden flare-up in inflation, they come with health warnings. Not all index-linked bond funds are the same. Take the same care when choosing between them as with a sharp axe when chopping wood.

The rest of this post is about understanding what you’re getting into and how to avoid the big bond fund pitfalls.

Bond aid

We favour high-quality government bond funds because they’re the best diversifiers of equity risk. In other words, when equities are down a lot, these types of bonds are the most likely to be up.

By high-quality we mean funds that are dominated by government issued bonds with a credit rating of AA- and above. A sliver of BBB rated bonds in the fund is okay, too.

Short, intermediate, and long refers to the average maturity date of the bonds held by the fund.

Maturity refers to the length of time a particular bond pays interest before the issuer redeems the bond in full.

A bond fund’s average maturity – reflecting all the bonds it holds – influences its level of risk. We explained how that works in our piece on bond duration [6].

Here’s the cheat sheet on how average maturity influences bond behaviour:

Short bond funds

- Short bonds are less volatile. That is, they experience smaller swings in value (up or down) as interest rates change.

- However, that makes them less beneficial in a recession, because they don’t make the capital gains that intermediate and long bonds do when interest rates fall.

- Short bonds also offer the lowest expected return [7] over time. Less risk, less reward.

- Maturities range between zero and five years. Look up your short fund’s average maturity figure on its web page. It’ll be somewhere between 0 and 5.

Long bond funds

- Long bond values are the most volatile. You can experience a significant capital gain when interest rates fall, or a loss when interest rates rise.

- That typically makes long bonds more beneficial in a demand-side recession.

- They offer the highest expected return over time (for bonds). More risk, more reward.

- Long bond funds are dominated by maturities over 15 years. Average maturity is likely to be 20+.

Intermediate bond funds

- Intermediate funds are the Goldilocks helping of bonds, versus the short and long varieties.

- They are somewhat risky, moderately helpful in a recession, and offer a middling long-term expected return.

- Intermediate funds hold bonds across a wide range of maturities, from short to long, and everything in between.

- Average maturities range upwards of 8+ to the late teens, depending on the intermediate blend you pick.

Next time might be different. We’re describing here the typical behaviour of the various bond fund types. They are not guaranteed to work this way in the short-term or during every economic event. Learn more about bonds behaving badly [8].

Short index-linked bond funds

- Index-linked bonds offer unexpected inflation resistance that other bond types don’t have.

- Unexpected inflation means high inflation that consistently outstrips market forecasts. This is the most dangerous type of inflation for equities and non-index-linked bonds (often called nominal bonds).

- Index-linked bonds make payments that are pegged to official measures of inflation.

- This should make them useful in stagflationary recessions that hurt equities and nominal bonds.

- But you may have to stick to short index-linked bond funds for reasons explained briefly below, and detailed in our post about the index-linked gilt market’s [9] hidden tripwires.

Young investor bond fund selection considerations

Are you a young (ish) investor who wants to guard against the threat of a deep, deflationary recession? (Think Great Depression, Global Financial Crisis, Dotcom Bust, Japanese asset price bubble).

Then long government bond funds are the best diversifiers for you.

That’s especially the case if your portfolio is heavily skewed towards equities. (Say a 70% or higher allocation.)

Diversification decrees you want the bond class most likely to profit when your big equity holding crashes. That’s long bonds.

Meanwhile a 70%-plus equity portfolio is likely to be so volatile you probably won’t much notice the relatively wild swings of long bonds on top.

Consider the long bond trade-off carefully

The opportunity: Because you won’t withdraw cash from your portfolio for 30 years or more, you can ride out capital losses should bond yields rise [10]. But when the world is laid low by a major recession, you should capitalise on surging long bond values as interest rates tumble.

In this scenario, long bond gains cushion your portfolio from equity losses. We’ve seen bond funds do just that during past market slumps [3].

Later you can mobilise your bonds as a source of financial dry powder. You sell some bonds to buy more equities while they’re on sale – a technique known as rebalancing [11].

The threat: Long bonds can suffer equity-scale losses during periods of rising interest rates and when inflation lets rip. This risk has materialised with a vengeance in 2022.

This chart (from JustETF [12]) shows how one long UK government bond fund has dropped 36.5% year-to-date:

[13]

[13]Hardly an easy loss to shrug off! Even a young investor should think twice about long bonds given the current balance of risks – the strong possibility of prolonged rising inflation alongside interest rate pain.

That goes double if you’re the sort of person liable to get distressed by individual losses in your portfolio. (Versus viewing it holistically as a system of complementary asset classes that thrive and dive under different conditions.)

Intermediate high-quality government bond funds may offer a better balance of risk and reward for you.

Older investor bond fund considerations

Near-retirees or retired decumulators [14] have a trickier balancing act. That’s because you’re likely to withdraw funds from your portfolio in the near-term.

Short bond funds and/or (especially) cash won’t suffer from a rapid capital loss like long bonds can. So owning them means you’re less likely to face a shortfall that derails your spending needs.

Demand-side recessions are still a threat to a retiree’s equity-dominated portfolio. But adding long bond fund risk on top can ratchet risk to an unacceptable level when there’s less time to wait for a recovery.

Again, intermediate bond funds chart a better course between the threats of rising interest rates and insufficient diversification during a crisis.

But why not just stick to short bonds or cash?

The next chart shows why. This is how short, intermediate, and long UK government bond funds responded during the COVID crash:

[15]

[15]As equities caved during the early days of the crisis, long and intermediate bonds spiked almost 12% and 7% respectively.

Short bonds barely registered there was a pandemic on. Cash was similarly indifferent. So while these assets didn’t lose, they didn’t counterbalance falling equities much either.

On the right-hand side of the graph, you can see long bonds came out ahead, with intermediates and short bonds in the silver and bronze positions. Just as you’d expect in a deflationary slump.

Meanwhile – in the middle of the crisis – a whipsaw effect temporarily crumpled all gilts thanks to a sell-off by large investors desperate for liquidity.

It stands as a useful reminder that our investments rarely work like clockwork during a panic.

Inflation protection

There’s no one-and-done, slam-dunk solution to inflation risk.

Anyone who fears uncontrolled, high, and unexpected inflation should consider an allocation to short maturity, high-quality index-linked bond funds.

But young investors with a long time horizon could just inflation hedge [16] using equities.

That’s because the long-term expected returns of equities are higher than index-linked bonds, even after inflation prospects are taken into account.

Retirees, by contrast, are better diversified if their defensive asset allocation includes a slug of short index-linkers.

The twin thumbscrews of rising interest rates and inflation are torture for nominal bonds. Short index-linked bonds are better equipped to take the pain:

[17]

[17]- Blue line: This short global index-linked bond fund (hedged to GBP) has returned -1.1% since inflation took off.

- Red line: Our short, nominal UK government bond fund fared worse with a -6.4% return.

- Orange line: But the intermediate, nominal UK government bond fund did worse still. It took a -24% hit in the last eighteen months.

The index-linked bond fund has fared better than its two nominal bond counterparts in an inflationary environment. Just as you’d expect.

What’s surprising is that the index-linked bond fund is down at all. What happened to its vaunted anti-inflation properties?

Index-linked bonds can fall even when inflation rises

The problem is that index-linked bond fund returns are composed of two main elements:

- Coupon and principal payments that are linked to inflation

- Capital gains or losses that are determined by fluctuating interest rates and bond yields [10]

Interest rates can climb so quickly that the resultant capital losses can swamp an index-linked bond fund’s inflation payouts.

This is what has happened in 2022. Hence index-linked bonds haven’t protected our portfolios nearly as well as we’d hope.

In particular, long index-linked bond funds have been absolutely awful these past six months:

[18]

[18]The long index-linked bond fund (blue line) is down 26% vs -1.1% for the short index-linked bond fund (red line).

Why? Because the long index-linked bond fund is much more vulnerable to rising interest rates. Its underlying bonds – with their longer maturity dates – are subject to more volatile swings in value when interest rates yo-yo.

That makes a short index-linked bond fund a better analogue for inflation. Though it too suffers (smaller) temporary setbacks from rate hikes.

Which is why I keep saying choose a short index-linked bond fund [19].

And because there isn’t a short index-linked gilt fund in existence, you’ll have to choose a global government bond version, hedged to the pound.

Hedging to the pound (GBP) removes currency risk [20] from the equation.

Global government bonds or UK gilts?

You also face choosing between high-quality global government bond funds hedged to GBP or gilt funds, which are still AA- rated (at least for now).

We used to be agnostic about this choice. There are good intermediate index trackers [21] available in both flavours.

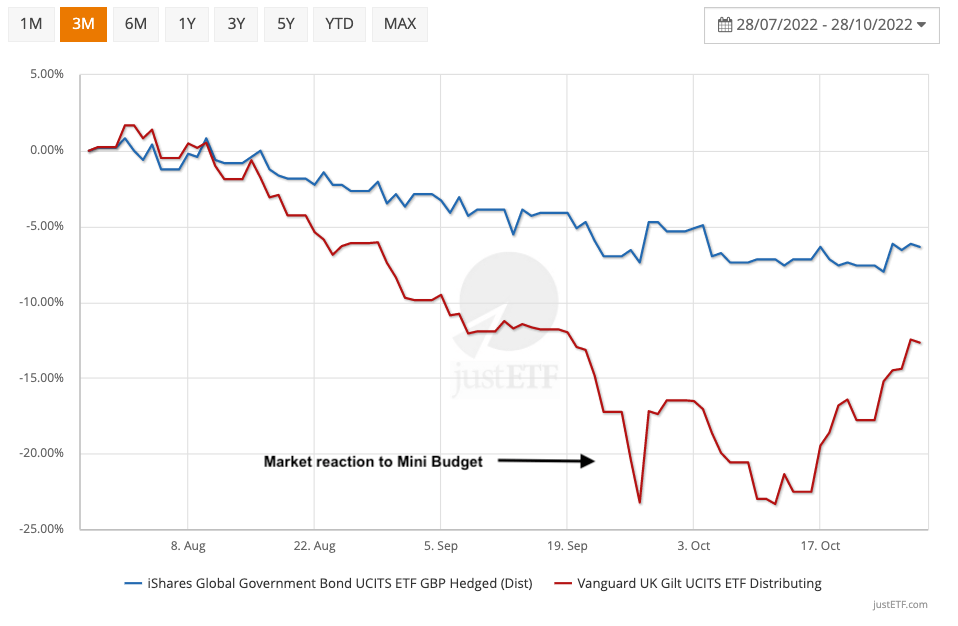

But then this happened:

[22]

[22]Gilts got pummeled relative to global government bonds when Truss and Kwarteng went on their bonkers Britannia bender [23].

UK government bonds have since climbed someway back out of the hole. Sanity has been restored, but this was a wake-up call. A stiff lesson in the danger of concentrating your risks in a single country.

We Brits proudly think of ourselves as members of the premier league of nations. So was this a one-off shocker or evidence we’re on the brink of relegation?

Your answer to that will determine whether you choose gilts or global government bonds.

Government bond funds or aggregate bond funds?

Another decision!

Aggregate bond funds cut high-grade govies by mixing in bulking agents like corporate bonds. The upshot is you gain a little yield but you give up some equity crash protection.

Crash protection from bonds is paramount in my view, therefore I favour government bond funds.

Our piece on the best bond funds [5] includes ideas for intermediate gilt and global government hedged to GBP bond funds.

And when you do come to choose a bond fund, this piece on how to read a bond fund webpage [24] may help.

Hedged or unhedged?

Should you choose a global bond fund, we think the argument is tilted in favour of selecting one that hedges its returns to the pound.

In other words, you’ll receive the return of the underlying investments unalloyed by the swings of the currency markets.

Bonds are meant to be a haven of relative stability in your portfolio. (Even though that hasn’t been the case for many of us in dystopian 2022.)

If you invest without hedging then you’re exposed to currency volatility – on top of whatever else might be knocking your bond investments around. Such currency moves may work for or against you. It’s lap of the gods stuff, despite what that nice man on YouTube says.

Hedging removes currency risk. Probably a good idea in the case of bonds though probably 1 [25] a bad idea for equities [26].

Hedging is particularly sensible if you’re a retiree who can do without their bond fund plunging just because some loony gets installed in Number 10 and tanks the pound.

Obviously UK-based investors don’t need to hedge gilt holdings. They’re valued in pounds in the first place.

Go West, young man (or bond-buying woman)

There is a nuanced argument that younger investors might want to choose to invest in unhedged US treasuries [27] – or at least that those young investors who are very hands-on with their portfolios could consider it.

That’s because US government bonds and the dollar often benefit from safe-haven status during a crisis. As such, returns from unhedged treasuries may temporarily outstrip any gains from gilts valued in sterling.

If they do then you can sell your treasuries and pop the proceeds into gilts, potentially adding a kicker to your overall return.

Historically, however, gilts have then reeled treasuries back in over time. So this ploy probably isn’t worth the trouble for proper passive investors [28].

How to choose a bond fund: model portfolios

Here’s some asset allocations devised in the light of all these ‘how to choose a bond fund’ ideas:

Young accumulators

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 80 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

Long bond funds are technically the best diversifier but we think that the threat of high inflation and continued rising interest rates makes them too risky right now.

There’s a more nuanced approach that involves holding a smaller allocation of long bonds while attempting to dampen the risk with an accompanying slug of cash. Read the Long bond duration risk management section of this piece [29] if you want to know more.

Older accumulators / lower risk tolerance

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

Equity risk is cutback while unexpected inflation protection is introduced. Note that index-linkers are nowhere near as effective as nominal bonds during a deflationary, demand-side recession.

Check out our other ideas on improving the 60/40 portfolio [29] and managing your portfolio [30] through accumulation.

Decumulators – simple

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 15 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 15 |

| Cash and/or short government bonds (Gilts) | 10 |

Decumulators use cash / short government bonds for immediate needs, equities for growth, intermediates as shock absorbers, and linkers for unexpected inflation defence.

Decumulators – max diversification

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 10 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 10 |

| Cash and/or short government bonds (Gilts) | 10 |

| Gold | 10 |

This portfolio adds gold [31] to the armoury of strategic diversifiers.

Gold isn’t an inflation hedge per se. But it has worked relatively well in two rising rate environments that have hammered nominal gilts [32] (the 1970s and now).

“I think interest rates will continue to rise…”

Okay, if you’re sure rates are headed higher then stick to cash.

Or if bonds seem too scary at the moment then stick to cash.

But remember that ever since the Global Financial Crisis ushered in near-zero interest rates, cash has done little more than protect your wealth in nominal terms.

You’ve lost spending power after-inflation with cash, whatever your bank balance says.

Look, we get it. 2022’s historic kicking for bonds has been so savage that even ten-year returns are lousy for many funds.

But it would be bold – to say the least – to bank on a repeat performance over the next ten years.

The expected returns from cash are worse than bonds over the long-term.

Cash is not a free pass.

If you don’t believe you can predict the future course of interest rates (you can’t) then put your faith in diversification.

If you’re still not sure, maybe split the difference: some cash, and some bonds.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

P.S. If you’d like to know more about bonds then check out these posts:

- How rising bond yields [10] improve returns over the long-term

- What bond duration [6] tells you about your fund’s risk level

- How interest rate shifts affect bond prices [33]

P.P.S. When we mention ‘interest rates’, we’re referring to bond market interest rates, not central bank interest rates. References to ‘yield’ mean yield-to-maturity. Please see our bond jargon buster [4] for more.

- We are saying “probably” here not because we can’t be bothered to consult a textbook, but because the case isn’t clear-cut and nobody knows the future.[↩ [38]]